Polish Women

There are many things Polish is known for such as wine production, religion, architecture, and a lot more. But apart from it, Polish is getting more and more popular because of Polish women. They are popular in many European countries and are known to be beautiful wives. This article aims at helping you to figure out what statements are true and what are not. First, let us try to find out the reasons for such popularity.

Why Polish Women are So Popular?

Polish girls are gorgeous

No doubt, a man wants his wife to possess stunning beauty. A man wants to rejoice over the appearance of his wife every morning and feel exultant. Polish girls fit this shoe as they have become initially popular among European men for their beauty. Whether it’s due to the fact they inherit beauty from their mothers or other factors, most Polish girls possess fair skin and rarely do makeup since they simply can't do without it.

Their friendliness and openness

The other attractive character trait inherent in Polish women is their artlessness. The acquaintance is always an important part of a relationship. Be sure ladies from Polish will enchant you by being sensible and modest. This is one of their most effective secrets of being so attractive. It’s just always pleasant to be with people who are sensible and therefore always take a hint.

Their intelligence

The sharpness of the mind is an attractive trait of a woman. Just from the first meeting, you will be able to appreciate the education and erudition of a Polish woman. For a long time, education in Polish was in decline. However, in recent years, it has been rapidly developing and producing intelligent ladies. This quality is incredibly important for marriage life, because very often, being at a party, your woman will be able to keep a conversation going and win over others. Also in this regard Polish women are incredibly purposeful and used to achieve success in education and career independently.

What are Polish brides like?

Undoubtedly, the strength of a marriage depends largely on how well you know your partner. This is why this article describes Polish wives as they are. In this paragraph, we will touch on the main character traits of Polish mail order brides.

Their devotion

The vision of a future family is very important for a typical Polish bride. That is why they initially set themselves up for a long marriage, which should not fall apart no matter what. There are many excuses to justify an unhappy marriage. However, Polish mail order brides always take the blame and analyze their mistakes in relationships. That is why they are not subject to sudden impulses, which cause quarrels, resentment and the collapse of the family.

Their relation with the baby

It is crucial for a man to understand that his wife will be a loving mother who will always be ready to give herself to children and provide for them. Polish brides belong to this type of woman. From the moment the child is born, they are ready to take a maternity leave, in order to fully take care of the child. This is due to the fact that they feel a huge responsibility for their child's life and well-being. In addition, the Polish woman will encourage in every way your contribution to the balanced development of the child.

Their desire to raise the child together

Unfortunately, it often happens that either because of the employment of one of the spouses or because of reluctance one parent participates in the life of the child much more than the other. You can be sure that this will never happen with a Polish bride. The fact is that they are very concerned about the welfare of the child and therefore support a balanced upbringing of the child. They can also offer various types of entertainment in order to bring all family members closer together. In addition, even with the arrival of a second child, Polish brides will never neglect the first one. That is, no matter how many children you have, everyone will be fulfilled.

How to date Polish girls?

It would be unreasonable to suggest a certain way of courting a Polish girl, but one can highlight important points.

Take an interest in her worldview and family

You need to take an interest in what your girl lives for and what finds her niche in order to show that you value her worldview. In addition, you will be able to learn a lot of interesting things and highlight them for yourself. Thus, by asking her about various things, she becomes interested in your opinion, and you start an open and warm conversation. Also at some point in the relationship, it may come to meeting her parents. The opinion of parents about a potential spouse is very valued by a girl in Polish. That is why you should be as open and friendly as possible with her parents so that they understand that you want to bring your girl only happiness.

Please her with little things more often

Polish women always notice your pleasant initiatives. That is, for them, say, help with carrying bags can be no less valuable than some expensive gift. Keep this in mind and light up your partner's life more often, making her unforgettable surprises. For example, you can make a romantic evening by yourself, having previously varnished the apartment up and cooked dinner. The more often such initiatives are shown on your part, the stronger your feelings for each other.

Always adopt responsibility

If there is any trouble, it is very important to show yourself as a real man and take responsibility for yourself. You must show the Polish girl that you are always ready to stand up for her and be supportful. Try to be a gentleman in small things. For example, you can help take off her outerwear, pay the bill, show up on a date with flowers, and so on. Your attitude towards the small things shows one towards the big things for a Polish girl.

How to seduce Polish girls

Place the focus on your priority

One of the first tips to note is to try, if you feel that you’ve reached intimacy with her, to ask her more often about her vision of a future family and married life. You can be sure that she will understand your hints. In this unobtrusive way, you can turn your communication towards a serious relationship. In addition, if you have already planned to start a family, try to spend more time talking about various aspects of marital life. This way, your Polish lady will get how important it is for you to build a happy family.

Be honest from the beginning

It is very important in any conversation to be as frank as possible and never withhold anything, as in the future it may cause distrust. Moreover, your conscience will be clear, because you will understand that you have nothing to hide from your future wife. This will appeal to the Polish woman and she will show mutuality.

Know your direction

Since you want to act like a real man, it is important to show your woman that you know your aspirations and what you want to achieve in life. Be as honest as possible when setting priorities for the future. This way, your partner will be realistic about the future life with you. You need to make sure you both are on the same page from the beginning and understand what each of you wants from the relationship. Just by taking such a step, your girl will completely change her attitude to you in a more positive way.

Of course, live communication has a number of advantages, but it is quite time-consuming. Therefore, dating sites are often a great option to build communication with a girl that you like without spending a lot of time. In the next paragraph, we’re going to give you a few pieces of advice on choosing the right dating platform.

How to find a reliable Polish dating platform?

Make the list of your favorites

Polish women are very popular among Slavic men, so you can often see a lot of Polish mail order brides among other Slavic women on international dating sites. So you can start your dating site search by browsing the Internet for the most acclaimed international platforms. It will be sufficient for you to analyze 10-15 major sites to make the list. After that, you’ll need to assess each and drop out ones you don’t like. This way, you’ll have the list of sites that interest you.

Get information from your friends

Once you have a list of sites you are interested in, you can contact your friends or acquaintances who have dealt with dating sites and ask for their opinions or advice. You may learn that some services are better left out or something should be avoided. You will definitely benefit from the help of those who have experience in finding love through dating sites.

Contact the customer support directly

The customer service is a kind of indicator that reflects the attitude to the audience as a whole. This is why you can once again weigh all the pros and cons and decide for yourself whether a particular service is suitable for you. You will be able to directly ask questions about refund and privacy policies as well as find out other important nuances.

Polish brides

To sum up, let us compare Polish and American women. In the paragraphs below we will highlight the main differences between Polish and American ladies. These differences will be directly significant for the marriage.

Polish ladies are much more sensible

As mentioned earlier, Polish girls are down-to-earth and will always help and cheer you up. They are comfortable with your failures. The main thing for them is to understand that you strive and want to be better. American girls, on the contrary, are always very demanding of men and expect impressionable achievements from them. Because of this, they transfer responsibility for all failures to you. They also tend to blame their spouses for their troubles.

Polish ladies are truly dedicated to the family

American girls are much more selfish. As a result, they constantly want all the attention to go to them. For them, a child is not a reason for happiness, but an obstacle to receiving attention and love. This is one of the main reasons why American women refuse to have more than one child. Polish women, on the contrary, are always happy to have and raise children, as well as to involve you in the process of raising a child in every possible way. They love spending time with their family and see this as their main goal in life.

Polish brides won’t leave you

No matter what happens, Polish women will never go for divorce, because for them it is like putting an end to the welfare of the child. They are always tranquil and solve conflicts in a measured way and without venomous remarks. American women are much more impulsive, and as a result, often quarrel over trifles. As they are selfish, even if the fault is on their side, they are waiting for your forgiveness. Therefore, Polish women are much more reliable and loving wives than American women.

Finally, we would like to wish you diligence in building relationships with your loved one. Polish women are very gentle, modest and loyal. It will be pleasant to build a happy and fulfilling family with them. Dating sites can be very useful in this and save you a lot of time. Try things out and enjoy life with a Polish wife.

100 remarkable women from Polish history to celebrate 100 years of women’s suffrage

Exactly 100 years ago Polish women gained the legal right to vote! On 11 November 1918, after more than 123 years of partitions and foreign rule, the Polish people regained independence and formed the recreated Polish state. On 28 November 1918, not long after forming the first legal structure of the reborn country, Poland passed an electoral law allowing women to vote and to hold public office. Polish women were among the first in Europe to gain these rights.

The first independent elections to the Legislative Sejm (the temporary parliament between 1919-1922) were held at the beginning of 1919, and the first women were elected were Zofia Sokolnicka, Irena Kosmowska, Franciszka Wilczkowiakowa, Zofia Moraczewska, Maria Moczydłowska, Gabriela Balicka-Iwanowska, Jadwiga Dziubińska, and Anna Piasecka. Those eight female MPs made up around 2% of the newly formed Sejm.

The Polish Senate was (re)created in 1922. Those elections allowed four women to hold the position of senator (out of total of 111 senators). These were Aleksandra Karnicka, Dorota Kłuszyńska, Helena Lewczanowska, and Józefa Szebeko. Local councils were, on average, about 15% female. It wasn’t much, but it made an impact on women’s awareness at the time.

What would be a better occasion than today to celebrate the stories of notable women throughout history? Read on to learn more about 100 Polish women and the ways they shaped their country and the world…

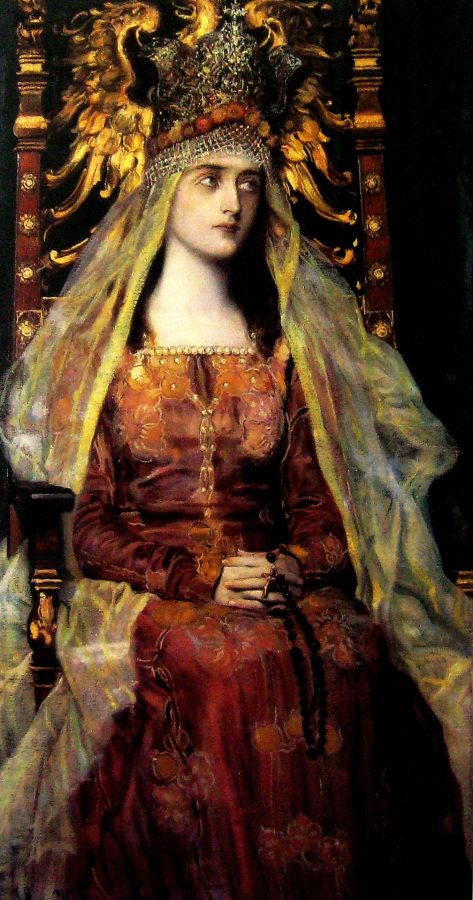

1Jadwiga of Poland (1384-1399): crowned with the title of ‘King’ during an era when female rulers were relatively uncommon in Europe. She donated most of her personal wealth (including royal insignia) to charity and education, funding and restoring many schools and hospitals, and focused on maintaining peace and development during her rule.

2Nawojka(14th/15th-century): a semi-legendary woman known to attend studies at the University of Krakow (later known as Jagiellonian University) in the 15th century, which she entered illegally dressed as a boy. She is considered to be the first historically acknowledged female student and teacher in Poland.

3Magdalena Bendzisławska (17th/18th century): the first historically attested female surgeon in Poland. The dates of her birth and death are sadly unknown, and the main document confirming her existence and profession is a diploma issued by King Augustus II the Strong in the year 1697. She took over the role from her husband after he passed away, and she worked as the chief surgeon at the famous salt mine in Wieliczka.

4Maria Skłodowska-Curie (1867-1934): a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist, the first woman to win a Nobel Prize (which she got along with Pierre Curie and Henri Becquerel) – the only woman to win the prize in two fields, and the only person to win in multiple sciences. She was the first scientist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity, and she discovered the elements radium and polonium (the second named after her beloved home country).

5Emilia Plater (1806-1831): a Polish-Lithuanian noblewoman and a revolutionary fighter in the partitionedPolish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. She fought in the November Uprising of 1830, during which she raised a small unit and received the rank of a Captain in the Polish-Lithuanian insurgent forces. She is a national heroine in Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus, all formerly parts of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

6Irena Sendler (1910-2008): a nurse working in Warsaw when WW2 started. She joined the secret Polish resistance organization Żegota (codename for ‘Council of Aid to the Jews’). Despite many dangers she managed to rescue around 2,500 Jewish children by smuggling them out of the Warsaw Ghetto in occupied Warsaw, with the assistance of other members of Żegota. She’s on the list of the Righteous Among the Nations.

7Maria Szymanowska (1789-1831): a skillful composer and one of the first professional virtuoso pianists of the 19th century. She toured extensively throughout Europe during the 1810s and was one of the first pianists to perform a memorized repertoire in public. She is known as the first female composer from Poland to achieve both national and international recognition.

8Narcyza Żmichowska (1819-1876): a novelist and a poet, considered the precursor of the organized feminism movement in Poland. She inspired and co-founded a group called Entuzjastki (transl. Enthusiasts, which was a progressive association founded in 1830 in Warsaw by a group of women intellectuals in favor of equal rights for men and women). She was among many Polish intellectuals exiled after the failed November Uprising of 1830, after which she settled in Paris where she enrolled at the Bibliothèque Nationale, becoming one of the first women at the French Academy ever. Her first published novel was Poganka (The Heathen) in which she expressed interest in her female friend Paulina Zbyszewska. She was deemed an ‘eccentric’, smoked cigars (prohibited for women at that time), and refused to marry. After returning to Poland she founded a group of suffragettes in Warsaw, active in the 1840s, who also took part in anti-tsarist activities.

9Klementyna Hoffmanowa, nee Tańska (1798-1845): a writer, translator, and editor. She was the first woman in Poland to fully support herself financially from writing and teaching, and to consider herself primarily a writer by a profession. In 1831 she moved to Dresden and later to Paris, and was later called ‘the Mother of the Great Emigration’ (mass emigration or exile of the Polish elites, mainly to Western Europe, after the failure of the anti-tsarist November Uprising of 1830 during the time Poland was under Partitions).

10Simona Kossak (1943-2007): an award-winning scientist and ecologist. She spent over 30 years living in a hut in the Białowieża wilderness, Europe’s oldest primeval forest located on the border between Poland and Belarus where she grew close to the wild animals to the point it looked like she could understand their language, which gave her the nickname ‘witch’.

11Bona Sforza (1494-1557): a member of the Milan-based House of Sforza and became the Queen of Poland and Duchess of Lithuania by marriage to King Sigismund I the Old. She was known for her ambitious and energetic nature, ensuring a strong political position on the Polish court almost right from the beginning of her marriage. She was responsible for many economic and agricultural reforms implemented in Poland and Lithuania, eventually making her the richest landowner in the Grand Duchy.

12Princess Izabela Czartoryska (1746-1835): a writer, art collector, and prominent figure of the Enlightenment movement. Her palace was an important political and intellectual meeting place, known as one of the most liberal and progressive court in the pre-Partitioned Commonwealth. She was the founder of Poland’s first museum, which she called the ‘Temple of the Sibyl’ or ‘Temple of Memory’ (later moved to Krakow where it exists under the name of Czartoryski Museum).

13Countess Karolina Lanckorońska (1898-2002): an art historian and philanthropist. During WW2 she was an anti-Nazi and anti-communist resistance fighter of the Polish underground, and survived a German concentration camp for women (as a political prisoner). After the war she refused to live in Poland under the communist rule and spent most of her life abroad as a political émigré. She inherited her family’s enormous art collection, which she donated to the Polish state only after 1989 – after Poland underwent a democratic transition.

14Elżbieta Zawacka (1909-2009): a Polish university professor, scouting instructor, SOE agent, and freedom fighter during WW2 (using the codename ‘Zo’). She was the only woman in the elite special unit Cichociemni (‘Silent Unseen’) of the Polish underground, served as a courier carrying letters outside of the German-occupied Poland, and fought in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising.

15Irena Kempówna-Zabiełło (1920-2002): a skilled pilot and renowned glider. In 1949 and 1950 she established two world speed records for women: over a triangular course of 100 km and over a straight distance of 100 km.

16Elżbieta Sieniawska (1669-1729): a noblewoman, Grand Hetmaness of the Crown, and renowned patron of arts. She was described as a ‘lady of great wisdom, reason and shrewdness’, and she was deployed by her husband on diplomatic missions, duties, and obligations that he could not manage. As an influential woman politician in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth during the reign of Augustus II the Strong, she was deeply embroiled in the Great Northern War and in Rákóczi’s War for Independence. She was considered the most powerful woman in the Commonwealth and called the ‘uncrowned Queen of Poland’.

17Michalina Wisłocka (1921-2005): in the 1970s published the first guide to sexual life in communist countries, focusing on women’s needs. She fought for equal rights for women in a bid to fully participate in public, political, and economic life at that time.

18Tamara de Lempicka (1898-1980), born Maria Górska: a renowned painter of the Art Deco movement and gained international fame for her decorative portraits. She is known for her unconventional style of self-expression, and her art manifested bisexual, bold, liberated female sexuality.

19Zofia Stryjeńska (1891-1976): a painter, graphic designer, illustrator, and stage designer, one of the best-known Polish women artists of the interwar period. In 1911 she was briefly studying abroad at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where she enrolled using the name of her brother and dressed like a boy, because at that time the academy did not accept women. She grew in fame in Poland during the interwar period for her style inspired by the Polish folklore and Slavic paganism.

20Jadwiga Grabowska (1898-1988): nicknamed the ‘Godmother of the Polish fashion industry’ during communist rule. She promoted the modern ‘tomboy’-ish style of the 1950s and 1960s and was responsible for persuading the state-owned textile industries to produce a wide range of colorful fabrics available for common women, coming under constant criticism from supervisors and governmental authorities.

21Pola Negri (1896-1987): a stage and film actress during the silent and golden eras of Hollywood and European film, famous for her femme fatale roles. She was the first European film star to be invited to Hollywood and became one of the most popular actresses in the American silent film era. She started several important women’s fashion trends at that time that are still staples of the fashion industry.

22Maria Konopnicka (1842-1910): a poet, novelist, children’s writer, translator, journalist, and activist for women’s rights and for Polish independence under the Partitions, as well as an activist against the repression of ethnic and religious minorities in Prussia. Her life was turbulent, and her sexual orientation is widely speculated on by modern historians. After an unhappy marriage, she spent most of her late life living in a romantic relationship with the painter and feminist Maria Dulębianka.

23Maria Dulębianka (1861-1919): a social activist, feminist, painter, writer, and publicist. She was a prominent representative of the suffragette movement. She promoted women’s right to political participation and in 1908 enrolled herself as a candidate to the Galician Parliament (in the Austrian partition of Poland), where she was denied ‘due to formal reasons’. Her social work included founding of many children’s nurseries and kitchens for the poor, as well as setting up a help and activity club for homeless street kids. She was known to wear ‘masculine’ clothes.

24Maria Dąbrowska, nee Szumska (1889-1965): a writer, novelist, essayist, journalist, and playwright, author of the historical novel Noce i dnie (Nights and Days). She was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature four times. She specialized in the themes of human rights and human potential for development under life hardships. In her personal life, she is considered one of a few historically-confirmed Polish bisexuals. She maintained long-term open relationships – first a marriage with publicist Marian Dąbrowski until his death in 1925, then a concubinage with painter Henryk Szczygliński until his death in 1952. She spent the remaining years of her life living in a romantic relationship with a writer Anna Kowalska (also a widow at that time), whom she had first met during the WW2 period, when they had fallen in love. In her articles published for the Polish press during the interwar period she openly advocated tolerance for homosexuality and diversity of society.

25Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969): a composer and violinist. She is only the second Polish female composer to have achieved national and international recognition. She belonged to a large group of Polish composers from the interwar and post-war years creating in the neoclassical style. Despite constant pressure from the postwar communist government, she never composed any socialist realist work on their orders.

26Anna Jagiellon (1523-1596): the Queen of Poland and Grand Duchess of Lithuania. Despite multiple proposals, she remained unmarried until the age of 52. Then she was elected, along with her then-fiancé Hungarian noble Stephen Báthory, as the co-ruler of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Their marriage remained rather a formal agreement for the following 10 years, until the death of Báthory. She didn’t take the opportunity to claim the throne for herself. During her reign she spent most of her time in Warsaw on local administrative matters and sponsoring construction works, adding greatly to the development of the city.

27Irena Krzywicka (1899-1994): a controversial Polish Jewish feminist, writer, translator, and activist for women’s rights. During the interwar period she became one of the most famous feminists in Poland, spreading knowledge about sexual education and birth control. She was considered a scandalist at that time as, she talked openly about abortion, women’s sexuality, and homosexuality.

28Helena Modrzejewska, known also as Modjeska (1840-1909): a renowned actress specializing in Shakespearean and tragic roles. She emigrated to the USA in the 1870s where, despite her imperfect accent, she achieved great success, eventually gaining a reputation as the leading female interpreter of Shakespeare on the American stage. She was a women’s rights activist, describing the difficult situation of Polish women under the Russian- and Prussian-ruled parts of Partitioned Poland. Her speeches led to a Tsarist ban on her traveling to Russian territory.

29Hanka Ordonówna (1902-1950), born Maria Anna Pietruszyńska: a singer, dancer, and actress, one of the main stars during the interwar period in Poland. In 1931 she became a countess by marriage to Michał Tyszkiewicz, which made her an adored legend among lower classes of society who dreamed about a similar romantic life. Her career ended with the outbreak of WW2. She was arrested a few times as a political enemy and eventually sent to a gulag (Russian labor camp) in Uzbekistan where her chronic lung disease worsened dramatically. She was eventually evacuated to Beirut, where she stayed until her death, hoping to fight the disease.

30Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska (1891-1945): a renowned dramatist and poet in Poland, known as the ‘queen of lyrical poetry’ of the interwar period and the ‘Polish Sappho’. She established herself as one of the most innovative poets of her era, writing about many taboo topics such as abortion, extramarital affairs, and incest, which provoked numerous scandals. Her plays depicted her unconventional approach to motherhood, which she understood as a painful obligation that ends mutual passion. She spoke in support of a woman’s right to choose. She has a minor planet named after her, thanks to the Czech astronomer Zdeňka Vávrová.

31Barbara Radziwiłł (1520/23-1551): briefly the Queen of Poland and Grand Duchess of Lithuania as the consort of King Sigismund II Augustus (the last male monarch of the Jagiellon dynasty). They married in secret in 1547, after a few years of a love affair, causing a huge scandal. Her life became surrounded by many rumors and myths, and she became the heroine of many legends that inspired numerous paintings, literary works, and films.

32Maria Wittek (1899-1997): a soldier promoted to brigadier general in the Polish Army, the first woman ever to acquire that rank in Poland (but only in 1991, after the collapse of the communist government). At the age of 18 she joined the underground Polish Military Organization (Polska Organizacja Wojskowa) and completed the NCO (non-commissioned officer) training course. During the First World War she fought against the Bolsheviks as a member of the Voluntary Legion of Women. Between 1928-1934 she was the commander of the Female Military Training (Przysposobienie Wojskowe Kobiet – an organization training women for military service. During WW2 she became the commanding officer of the Women’s Military Assistance Battalions and fought in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. After the war she initially returned to her previous position as a head of the women’s military division, but in 1949 she was arrested by the communist authorities and spent several months in prison. After her release she worked in a newspaper kiosk. She never married.

33Maria Kazimiera d’Arquien (1641-1716), born Marie Casimire Louise de La Grange d’Arquien (and known in Poland by the diminutive name ‘Marysieńka’): the Queen Consort to King Jan III Sobieski. They were remembered as a compatible couple, rare in those times for high-status marriages. Their love letters reveal authentic feelings between the loving pair, but also their reflections on contemporary issues and difficulties, as well as down-to-earth matters concerning the royal household and little day-to-day decisions made by the monarch, who often consulted his wife about them.

34Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017): a sculptor and fiber artist, widely regarded as one of Poland’s most internationally-acclaimed artists. She’s known for her experimental sculptures, such as the series called Abakans: gigantic three-dimensional fiber works created in the 1960s that placed her in the international art world as one of the greatest and the most influential figures of that time. She created many large-scale projects such as the art installation Agora, consisting of 106 headless and armless iron sculptures located in Grant Park in Chicago.

35Anna Jabłonowska (1728-1800): a magnate and politician, referred to as one of the most significant women of 18th-century Poland. She was known for remarkable activity on her estates, introducing numerous management reforms and funding hospitals, factories, schools, and a printing press, all with the wellness of the people living on her estates in mind. She was known for her personal interests in science and botany. Her naturalist collection was one of the best in Europe.

36Olga Boznańska (1865-1940): a notable painter combining the impressionism and realism movements. She was known for her unique style and intimate portraits, emphasizing the spirituality of her models. She was widely acclaimed during her lifetime and today is regarded as one of the most significant Polish painters.

37Anna Dorota Chrzanowska (17th century): became a heroine of the Polish–Ottoman War (1672–76). She was the second wife of Captain Jan Samuel Chrzanowski. During the war they were stationed in Trembowla Castle, besieged by the Ottoman Turks. The castle managed to withstand many attacks, and the defenders underwent an internal crisis only after several days when shortages of food and water became severe. The captain decided to surrender, but his wife disagreed with his decision – she urged the defenders to carry out a daring attack on the Turkish positions, which is said to have raised the morale among the Poles greatly, and led the soldiers out herself, resulting in heavy losses among the Ottomans. Due to her act she has been called the ‘Polish Joan of Arc’.

38Anna Rajecka (c.1762-1832), later known as Madame Gault de Saint-Germain: a portrait painter and pastellist, recognized for her talent and raised as a protégé of King Stanisław August Poniatowski. She was one of a few women who frequently attended the king’s famous Thursday Dinners, and therefore she was rumoured to be his illegitimate daughter or his mistress (neither true as far as historians have researched). In the early 1780s, she was enrolled at the king’s expense at the art school for females at the Louvre in Paris and stayed in the city after falling in love and marrying a French miniature artist. She became the first Polish woman to have her work presented at the Paris Salon.

39Jadwiga Szczawińska-Dawidowa (1864-1910): an activist, publicist, and teacher. She founded the so-called Flying University, an underground educational organization primarily for women. It operated in secret in private apartments in Warsaw (changing the location frequently – hence the university’s name) at the time when that part Poland was under control of the Russian Empire, providing educational courses outside the occupiers’ censorship at the time. During the 20 years of the university’s existence, around 5,000 women graduated from it, among them Maria Skłodowska – later a Noble prize winner.

40Countess Maria Walewska (1786-1817): a Polish noblewoman remembered most for her long-lasting affair with Emperor Napoleon I. According to his memoirs, Napoleon remembered her for her extraordinary beauty after only a brief meeting in 1806, and requested to meet her again. She was said to be pious for her time and status, and admitted to have forced herself to get involved with Napoleon for purely patriotic reasons. She sought to influence his Eastern European policy, and during the affair she convinced him to create the Duchy of Warsaw.

41Katarzyna Kobro (1898-1951): a notable avant-garde sculptor of the constructivist and abstract movements. She co-founded a few major Polish and international modernist artistic groups in the 1920s and 1930s. She signed a number of manifestos, including the early-modern Dimensionist Manifesto (concerning a “new conception of space and time”). She was most famous for her “spatial sculptures” – combinations of rigorously architectural structures, sculptural forms, and constructivist aesthetics.

42Zofia Nałkowska (1884-1954): a prose writer, dramatist, and prolific essayist. During the interwar period she became one of Poland’s most distinguished feminist writers of novels, novellas, and stage plays characterized by socio-realism and psychological depth. In her writings, Nałkowska boldly tackled subjects which were difficult and controversial at that time, such as eroticism.

43Jadwiga Sikorska-Klemensiewiczowa (1871-1963): a pharmacist, and one of the first official female students in the history of Jagiellonian University, after graduating from the underground Flying University. She became the first chairwoman of the General Association of Working Women in Poland.

44Scholastyka Ostaszewska (1805-1851?): a social activist and an underground independence activist. She belonged to the group Entuzjastki (a progressive association founded in 1830 by a group of female intellectuals in favor of equal rights for men and women). Around 1848 she was active in a female branch of the Polish People’s Spring movement, which fought for independence from Partitions. In 1851 she was put under strict police supervision by the Russian occupants. Her date of death is unknown.

45Alina Szapocznikow (1926-1973): a sculptor and illustrator representing the surrealist, nouveau realist, and pop art movements. She is mentioned among the most important Polish artists of her generation. She was born to a Polish-Jewish family and survived the Holocaust during the Nazi Germany’s occupation of Poland. That period of her life made a huge impact on her art. She created a visual language of her own to reflect the changes going on in the human body and introduced new sculpting materials and forms of expression.

46Zofia Daszyńska-Golińska (1866-1934): a socialist politician, suffragette, university professor, and early female senator in interwar Poland. She was a member of a number of leading feminist organisations, including the Little Entente of Women.

47Kazimiera Bujwidowa (1867-1932): a notable feminist and suffragette in Poland. She was involved in campaigns to improve general education and literacy in Warsaw and Krakow, and she organized the first Krakow Reading Room for Women. She is credited with starting the first junior school for girls and for campaigning for women’s admission to Jagiellonian University as students (as they got in 1897).

48Maria Kokoszyńska-Lutmanowa (1905-1981): a notable logician and author of studies in philosophy, methodology, epistemology, and semantics. For some years after WW2, she was viewed as dangerous enough by the communist government to be deprived of the right to teach philosophy, being able to teach logic only.

49Gabriela Zapolska (1857-1921): a novelist, playwright, naturalist writer, feuilletonist, theatre critic, and stage actress. She received the most recognition for her socio-satirical comedies in which she mocked the moral hypocrisy of the upper classes (she herself was born to a wealthy family of Polish landed gentry). Her most famous work, The Morality of Mrs. Dulska (written in 1906), became a key work in early modernist Polish drama. In it, she criticized the hypocritical double standard of sexual behaviours and two-faced family values.

50Stefania “Barbara” Wojtulanis (1912-2005): an experienced glider, balloon and motor aircraft pilot, and parachute-jumping instructor (she received licenses for all of the above before her 24th birthday). At the start of WW2 she was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant, assigned to the general staff of the Polish army, and flew missions to deliver fuel to the fighter brigade defending against the 1939 attack on Warsaw. She was evacuated to Great Britain in 1940 and later assigned to the Air Transport Auxiliary as a ferry pilot, where she logged over 1,000 hours of flying. She was twice awarded the Silver Cross of Merit for her services during the war and was honoured at the International Forest of Friendship with a plaque for her aviation achievements.

51Helena Mniszkówna (1878-1943): a novelist and author of several books popular in pre-war Poland. She debuted with the novel Trędowata (The Leper, 1909) that brought her to prominence and became one of the most famous Polish melodramas (later in the 20th century dramatised four times by different directors). In 1951 all of her works were banned by communist censors in People’s Republic of Poland due to their bourgeoisie content, which they deemed ‘may have been harmful for society’.

52Eleonora Ziemięcka (1819-1869): considered the first female philosopher in Poland. She bravely entered that field at the time it was reserved exclusively for men. She played a significant role in the history of Polish philosophical thought at the time, representing the so-called Polish religious thought (or Polish Messianism). Her Thoughts on the Upbringing of Women, published in 1843, was the first book in which the issues of reforming women’s education and their need to develop the mind were addressed.

53Maria Ilnicka (1825-1897): a poet, novelist, translator, and journalist. In 1863/1864 she took part in the January Uprising against the Russian Empire, as an archivist of the underground Polish National Government. She was promoting feminism and organic work. In 1865 she was the editor-in-chief of a weekly magazine for woman, Bluszcz.

54Wanda Rutkiewicz (1943-1992): a computer engineer and a mountain climber. She is known as the third woman, the first Pole, and the first European woman to reach the summit of Mount Everest, which she accomplished in 1978. In 1986 she became the first woman to successfully climb K2, what she did without supplemental oxygen.

55Zofia Rogoszówna (1881-1921): a poet, translator, and writer of children’s literature. She was the first female writer in Poland who adapted rural short stories and rhymes into the literature for children, which she compiled in three tomes over time. She is considered a valuable researcher of folklore.

56Jadwiga Piłsudska (1920-2014): a pilot. She obtained her first pilot’s licence in 1937 (at the age of 17), then her aircraft pilot’s license in 1942, and served in the Air Transport Auxiliary during WW2. As a daughter of the Marshal Józef Piłsudski, she remained in Great Britain after the war as a political émigré. She never accepted British citizenship and used a stateless person passport, valid for all countries in the world except the communist People’s Republic of Poland. She was able to return safely to her country only in 1990, after the collapse of the communist government.

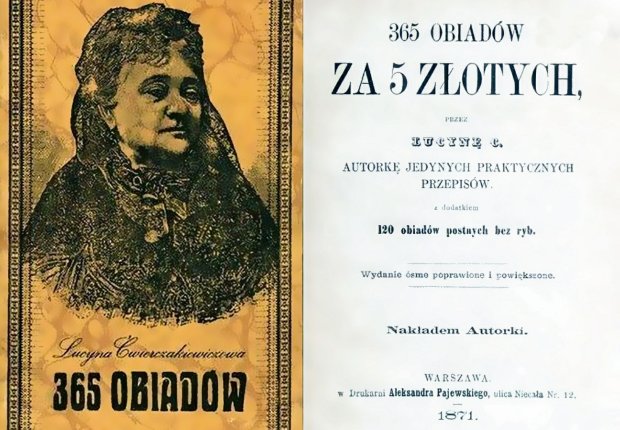

57Lucyna Ćwierczakiewiczowa (1829-1901): a writer, journalist, and author of several popular Polish cookbooks. After 1875 she devoted herself to preparing a yearly publication, Kolęda dla Gospodyń (A Housewife’s Carol), a calendar filled with cooking recipes, women’s suffrage ‘propaganda’, and short novels and poems. Her books made her the best-selling author in pre-war Poland. By the year 1924 her first cookbook was issued 23 times, with more than 130 thousand copies sold worldwide – more than all the books by the novelists and Nobel Prize laureates Henryk Sienkiewicz and Bolesław Prus combined had sold before that year.

58Anna Leska (1910-1998): a skilled pilot assigned to the Polish Air Force HQ squadron to fly liaison missions. After the 1939 defeat of Poland, she was evacuated to Great Britain and started ferrying aircraft with the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) where she eventually became a flight leader in charge of eight female ferry pilots, whom she instructed and assisted. She was one of only three Polish women serving in the ATA, and the only woman flying in the ATA to receive the Royal Medal.

59Zofia Sokolnicka (1878-1927): a social and political activist and member of parliament after Poland regained independence in 1918. During the First World War she worked as a courier – thanks to her outstanding memory, she could convey detailed political information and instructions without transporting any papers or notes.

60Izabela Elżbieta Morsztyn (1671–1756): a noblewoman, known for her political salon and role in the Familia(an 18th-century political party or fraction led by the House Czartoryski and allied families). In 1736 in Warsaw, she established the first political salon, where politicians met and the Familia party conferred. Women played a significant role in those meetings.

61Princess Konstancja Czartoryska (c.1696-1759): a noblewoman, later known as the mother of King Stanisław August Poniatowski. She was described as a serious person with an interest in education and politics, strongly devoted to her mother Izabela Elżbieta Morsztyn. She played a political role as a driving force within the Familia (political party led by House Czartoryski). She acquired a great influence within the family and led the political careers of her spouse and brothers. At the interregnum and royal election after the death of King Augustus II in 1733 she, alongside her mother and Zofia Czartoryska, were described as the most influential people in the Familia party, and she was represented her faction during negotiations (e.g., with a French ambassador).

62Stefania Sempołowska (1869-1944): an educator, social activist, and writer. At the age of 17 she passed the Teacher Patent at the Government Commission in Warsaw. She became a teacher and children’s rights activist, and was the author of many school books. During the Revolution in the Kingdom of Poland (1905) against the Russian Empire, she initiated a congress of delegates of the Polish teacher organizations, in which solidarity with the protesting common people was declared and the teachers decided to run lessons in the Polish language despite Russian prohibition.

63Faustyna Kowalska (1905-1938), born Helena Kowalska: a nun and mystic. Throughout her life, she reported having visions of Jesus and conversations with him, which inspired the Roman Catholic Divine Mercy devotion and earned her the title of ‘Apostle of Divine Mercy’. Based on her descriptions, the famous Divine Mercy image was created (she herself didn’t know how to paint, so she asked a few painters to recreate her vision on canvas, resulting in a few known versions of the scene). She was canonized in 2000.

64Helena Radlińska (1879-1954): a teacher, historian, and librarian, and the creator of the Polish school of social pedagogy. She promoted librarian pedagogy, readership, the creation of home book collections, and access to literature for different social groups (especially those from culturally underprivileged groups).

65Irena Morzycka-Iłłakowicz (1906-1943): a Polish second lieutenant of the National Armed Forces and an intelligence agent. During WW2 she was active in the Polish resistance movement and conducted military, economic, and intelligence reconnaissance. Her section was destroyed by the Nazi Germans, followed by numerous arrests of underground activists. She was captured in October 1942 and underwent harsh interrogations. She was rescued by fellow underground agents: first a bribed guard put her in the group of non-political prisoners to be transported to the Majdanek camp, from where she was rescued by agents dressed in stolen German uniforms. She continued her work as an agent. In the days before her death she was involved in an action against a radio contact point which supported Soviet Russian activities in Poland. She was murdered in 1943 in unknown circumstances after being summoned for an important meeting. Because the Nazi Germans often sent agents to family funerals (and other ceremonies), she was buried under a false name, and her husband participated in the funeral dressed as a gravedigger; her mother as a cemetery helper. Only in 1948 did her mother place a plaque with her true name on the grave.

66Maria Grzegorzewska (1888-1967): a Polish educator and teacher. She introduced and developed the special education movement in Poland. Maria Grzegorzewska worked out the original teaching method, called “the methods of working centers” focused on a creative work environment, which is still used in today’s special needs education. She was the first to start systematic research on pedagogical issues of the disabled in Poland.

67Agnieszka Osiecka (1936-1997): a poet, writer, author of theatre and television screenplays, film director, and journalist. She was a prominent Polish songwriter, having authored the lyrics to more than 2,000 songs, and is considered an icon of Polish culture.

68Barbara Sanguszko (1718-1791): a noblewoman, poet, translator, and moralist during the Enlightenment in Poland. She organised and hosted a salon in Poddębice, where the gathering of intellectuals, artists and politicians was modelled after French 18th-century salons. Sanguszko was known for her piety, generosity and philanthropy. She not only restored many Catholic churches and convents, but laid the foundations of new religious houses, including also Orthodox churches. Having in mind the future of her children and of the family estate, she took an active part in the political life of her country. She took it upon herself to attend parliaments and tribunals. Her soirées spawned the future theatrical initiatives of the Lazienki Palace. She hosted grand occasions in the Saski Palace, including illuminations, concerts and balls for dignitaries of the period.

69Barbara Kwiatkowska-Lass (1940-1995): a notable film actress. Raised in communist Poland, she took an opportunity to leave the country in 1959 to pursue her career in the West and starred in a few major Italian, German, and French films. She actively opposed the communist regime and cooperated with the United States-controlled Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, which transmitted anti-communist propaganda, information, and programmes free from censorship to Poland.

70Anna Iwaszkiewicz (1897-1979): a writer and translator, born to the family of a wealthy entrepreneur. She entered Polish artistic circles by marriage to Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz (then a novice writer) and they both were known for their turbulent bisexual orientation. During WW2 she and her husband actively helped rescue Jewish people from the Nazi German occupiers by hiding them, finding new shelters, and providing them with funds and with false documents. She is on Israel’s list of the Righteous Among the Nations.

71Katarzyna Ostrogska (1602–1642): a Polish–Lithuanian noblewoman, known as the founder of the city of Biała (modern Janów Lubelski). She was married to the nobleman and voivode Tomasz Zamoyski. Widowed in 1638, she took over management of the Zamoyski estates. In 1640 the king granted her the privilege to found the city of Biała, including the right to organize the government of the city and appoint its officials. She wrote several documents regulating life in her city.

72Alina Centkiewicz (1907-1993): a writer and explorer, as well as the co-author of many travel books (written with her husband). She was best known for her descriptions of the Antarctic Circle region. In 1958 she was the first Polish woman (and the sixth woman in the world) to explore Antarctica.

73Wanda Gertz (1896-1958): a soldier and independence activist. Born to a noble family, she began her military career in the Polish Legion during the First World War dressed as a man, under the male pseudonym of Kazimierz Zuchowicz, or ‘Major Kazik’. With the outbreak of WW2, thanks to her experience and skills she became an officer of an all-female battalion in the underground Home Army, where she took the codename ‘Lena’, and created a female division and sabotage unit. She was captured after the failed 1944 Warsaw Uprising and remained imprisoned in various German camps until the liberation by the US army in 1945. After the war she travelled throughout Germany and Italy in a search of displaced Polish women, joining the Polish Resettlement Corps. After demobilisation she worked in a canteen until her death.

74Ewa Szelburg-Zarembina (1899-1986): a novelist, poet, and screenplay writer, best known as the author of numerous works for children. She co-initiated a fundraising program that eventually led to the construction of the Children’s Memorial Health Institute, the largest and the most modern centre of paediatric care for children in Poland.

75Anna Kostka (1575–1635): a Polish–Lithuanian noblewoman. She inherited the city of Jarosław as well as several other areas from her mother. After being widowed in 1603, she lived an independent life as the manager of her and her children’s dominions. She financially supported the University of Jarosław, introduced the Benedictine Order to the city, protected the Jesuits, commissioned several (later famed) art objects for the churches, and became known for her charity toward the poor.

76Seweryna Szmaglewska (1916-1992): a writer, known for books for both children and adults alike. During WW2 she was arrested by the Nazi Germans in a łapanka (street roundup), and sent to the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp as a political prisoner. She survived three years in the camp, and after the war she was one of very few Poles to testify at the Nuremberg Trials. She collected her memoirs in a few books, the most famous being Smoke over Birkenau.

77Janina Lewandowska (1908-1940), born Janina Dowbor-Muśnicka: a second lieutenant in the Polish air force, devoted entirely to her flying career. After the outbreak of WW2 she was drafted for service in the 3rd Regiment, but her unit was taken hostage by Soviet forces in unknown circumstances. She was one of only two officers in the imprisoned group. She died in the infamous 1940 Katyn Massacre, and her remains were identified only in 2005.

78Wanda Błeńska (1911-2014): a tropical disease expert and missionary who succeeded in developing the Buluba Hospital in Uganda, an internationally recognized centre for leprosy treatment.

79Aleksandra Zagórska (1884-1965): an independence activist and soldier. During the First World War she commanded the women’s intelligence service in the Polish Legions. In 1918 she formed the female paramilitary organization Ochotnicza Legia Kobiet (Voluntary Legion of Women) and served as the organization’s commander. In her military career she was eventually promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. During WW2 she joined the resistance as part of the left-leaning Coalition of Independence Organisations. After the war she lived under the pseudonym ‘Aleksandra Bednarz’ to avoid the communist government’s persecution on account of her history of independence activism.

80Maria Nostitz-Wasilkowska (1858-1922): a painter and portrait artist, nicknamed ‘Charmante Polonaise’ by the upper classes. Her favourite medium was pastels, and she specialized in female portraits, valued for her ability to interpret the model’s psychology through subtle color and light. Her portraits were often described as ‘living and vibrant’, as if she caught the model in an ephemeral moment. She graduated with honors from the art academy in Saint Petersburg and paved her way to become a favourite artists of the elites in Saint Petersburg and Warsaw, travelling between those cities during her lifetime. Sadly, not many portraits by her have survived to the modern day.

81Lena Żelichowska (1910-1958): a dancer and actress, one of the most popular in interwar Poland. She debuted on screen in 1933 and quickly gained popularity, becoming one of the most promising film stars in Poland. Before the outbreak of WW2 she managed to appear in 14 movies and starred in numerous theatre plays. During the early stages of the war, she and her husband Stefan Norblin (a notable art deco artist) escaped Poland, and only his reputation as a painter opened many doors, including those of the royal family in Iraq and the Maharajahs in India, where they lived until the end of the war. In the late 1940s they eventually settled in the US. Due to her accent she never managed to return to acting.

82Krystyna Skarbek (1908-1952), also known as Christine Granville: a WW2 spy working for the British Special Operations Executive. She became celebrated especially for her daring exploits in intelligence and irregular warfare missions in Poland and Nazi-occupied France, and she was one of the longest-serving of all Britain’s wartime women agents. After the war, Skarbek was left without financial reserves or a native country to return to (she didn’t recognize the communist government in postwar Poland). Her life is said to be an inspiration for the fictional characters of Vesper Lynd and Tatiana Romanova in the James Bond novels Casino Royale (1953) and From Russia, with Love (1957).

83Teresa Bogusławska (1929-1945): a promising Polish poet and a participant in the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. She joined the Polish scouts’ underground resistance movement at the age of 12. In 1944 (aged 15) she was arrested by the Nazi Germans while pasting independence slogans on German posters. She was imprisoned and tortured during questioning, and suffered badly from tuberculosis after barely three weeks spent in prison. She was freed, but her health never recovered. During the Warsaw Uprising later that same year, she helped the insurgents by sewing uniforms and arm bands. She died early in 1945, aged 16, from meningitis caused by the tuberculosis.

84Anna Pustowójtówna (1838-1881): a noblewoman, activist, and soldier, famed for her participation in the January Uprising. She identified herself fully as a Pole despite being a child of a mixed Polish-Russian couple, her father being a high-ranking Russian general. She became an activist for the cause of the Polish independence and sided with the Polish troops during the 1963 January Uprising. She disguised herself as a male soldier and went by the alias ‘Michał Smok’ (literal translation: Michael the Dragon). She fought as an assistant to the general Marian Langiewicz. She took active part in a few battles, such as the Battle of Małogoszcz, Battle of Pieskowa Skała, Battle of Chroberz, and Battle of Grochowiska, becoming a living legend of the Uprising (much like Emilia Plater, who became a symbol of the November Uprising c. 40 years earlier).

85Maria Piotrowiczowa (1839-1863): a January Uprising insurgent, participating in the Battle of Dobra (the Łódź province). Upon news of failures of the ongoing uprising, she decided to support the fighters, cutting her hair and putting on a men’s insurrectionary garment. She joined a small troop led by a man from a nearby manor. At the beginning she was on an auxiliary duty, but when the military situation deteriorated she declared her intention of joining front-line duty. In February of 1863 the Russian troops took her unit’s camping site by surprise. She fought to the very end and stayed on the battlefield, rejecting the suggestions of surrender given to her by Russian officers. With a remaining small group of young people, she bravely defended the troop flag donated to the unit by women from the city of Łódź. Armed with a revolver and a scythe, encircled by Cossacks, she killed one, wounded another, and killed the horse under yet another one before dying from their hands. Her body was pricked with pikes and sabres. The tragedy was magnified by the fact that Maria was pregnant at that time.

86Natalia Zarembina (1895-1973): a writer and journalist. During WW2 she was also a participant of the underground resistance in occupied Poland: she served as an activist of the Polish Socialist Party – Freedom, Equality, Independence (a WW2 underground resistance party) and as a member of the underground organisation Żegota (Council of Aid to the Jews). In late 1942 she published the book Obóz śmierci (Eng. Death Camp), released by the underground press, which was the first document telling about the German concentration camp of Auschwitz. She included firsthand information based on reports of refugees and people dismissed from the camp. Her book was translated to English in the following year, becoming one of the first reports of the Nazi German atrocities in the occupied Poland, followed by the famous Pilecki’s Report.

87Eliza Orzeszkowa (1841-1910): a journalist, social activist, novelist, and leading writer of the Positivism movement during the late era of the Partitions of Poland. In 1905, along with Henryk Sienkiewicz, she was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature. She authored over 150 powerful works dealing with the social conditions of her occupied country.

88Teofila Chmielecka (1590–1650): a Polish military spouse, married to Stefan Chmielecki. She was known for her dedication to the military ideals and for maintaining the Spartan lifestyle necessary in the army, and came to be known as the ideal role model of a military wife. She displayed her personal courage on several occasions, earning the nickname “The Wolf of the Frontier”.

89Teofila Ludwika Zasławska (c.1650-1709): a noblewoman known as perhaps the most significant landowner in Poland in her time. She was the daughter of Katarzyna Sobieska (sister of King Jan III Sobieski) and an heiress of the Ostrogski family. She was married twice: to the Great Crown Hetman Dymitr Jerzy Wiśniowiecki, and after his death to Prince Józef Karol Lubomirski. Upon her first husband’s death, she inherited large holdings that included the Baranów Sandomierski Castle (not without a legal fight for those rights). After the death of her brother she became the only heir to one of the largest estates in the Commonwealth, the Ostrogski Ordination, which included several dozen towns. As a result of her second marriage, the large landed estates of the Ostrogski Ordination in Poland were transferred to the Lubomirski family. The combined fortune of the Zasławskis and Lubomirskis would become for a time the largest fortune in the Commonwealth. Her second husband had an ongoing extramarital affair which became public, resulting in her attempting to declare him legally insane. They were formally separated until his death in 1702. During the last years of her life she was involved in charity work, including management and development of schools.

90. Rozalia Lubomirska (1768-1794): a noblewoman, most noted for her death. At the age of 19 she was married to Prince Aleksander Lubomirski. They travelled to France but, unhappy in her marriage, she decided to divorce her husband and did not accompany him on his way back to Poland. The time of the French Revolution met her in Paris. She was arrested along with her child and tried for alleged conspiracy against the Revolution. As a result, the 26-year-old princess was sentenced to death and soon beheaded by guillotine, although her guilt was (and remains) widely questioned. The death of a Polish national caused much concern among the Polish nobility who, prior to the Reign of Terror, openly cheered the Revolution. Among those who spoke in her defence was Tadeusz Kościuszko. After her death, Rozalia became the subject of legends. According to one, her ghost appears in the Lubomirski Palace in Opole Lubelskie.

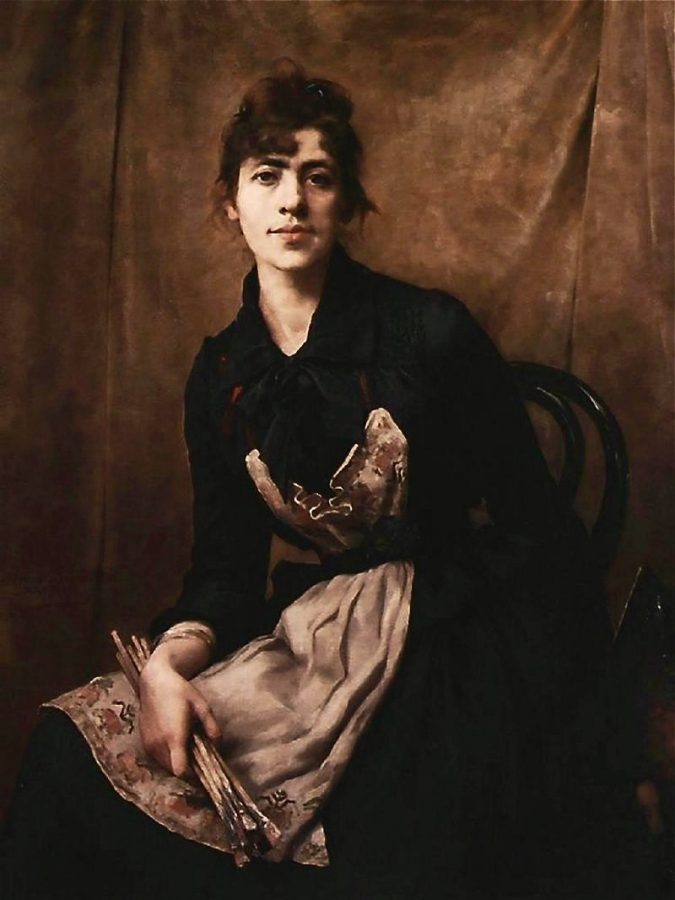

91. Anna Bilińska-Bohdanowicz (1857-1893): a painter known for her portraits, painted with a great intuition. Her Self-Portrait with Apron and Brushes (1887) developed a new self-portrait pose by placing the artist in front of a model’s backdrop, thus showing that she is her own model. She was internationally recognized during her lifetime and studied art in Paris. After returning to Poland she intended to open a painting school for women in Warsaw, which would have mimicked the practices of the Parisian academies. However the project was stopped short when the artist fell ill with a heart condition.

92. Zofia Rydet (1911-1997): a professional photographer best known for her project ‘Sociological Record’, which aimed to document every household in Poland. She began working on that project in 1978 at the age of 67, taking an enormous collection of nearly 20,000 pictures until her death in 1997. The photos show various informal scenes in different ordinary Polish households, often with the owners among their belongings.

93. Teofila Certowicz (1862-1918): a sculptor and artist. For a brief time she opened and managed her own art school for women in Krakow, the first one of that kind in the city, and invited prominent artists such as Włodzimierz Tetmajer and Jacek Malczewski to teach the girls in her school.

94. Wanda Telakowska (1905–1986): an artist best known as the founder of Warsaw’s Institute of Industrial Design. She was a member of an Arts and Crafts collective that encouraged a new artistic identity which included folk art. After the WW2 she joined the communist government in Poland, creating the Bureau of Supervision of Aesthetic Production. As the head of the Bureau, she commissioned artists to design many mass-produced Polish goods, under the motto ‘Beauty is for every day and for everybody’. However, some artists were suspicious of collaborating with the communist government during a time of continued political conflict. Ultimately, the Bureau was shut down, as the value of artist designs was not convincing enough to factory owners. She went on to create Warsaw’s Institute of Industrial Design in 1950 and served as its first director. In this role, she ‘invited artists, ethnographers, art historians, pedagogues, sociologists, and enthusiasts of folk art to contribute to her institute’s efforts to develop new forms of sociologist culture in collaboration with working women, peasants, and youth.’ She’s known as a promoter of the term ‘industrial design’ in Poland. Some Polish artists have dismissed her legacy as a failed attempt to work with communists.

95. Zofia Baniecka (1917-1993): a member of the Resistance during WW2. In addition to relaying guns and other materials to resistance fighters, she and her mother rescued over 50 Jews by hiding them in their home between 1941 and 1944. Later, she was an activist with the Intervention Bureau of the Polish Workers’ Defence Committee in 1970s. She and her husband were active participants in the Solidarity movement in the 1980s, distributing underground media. In her professional capacity, Baniecka was a long-time member of the Warsaw chapter of the Association of Polish Artists and Designers.

96. Maria Kotarba (1907-1956): a courier in the Polish resistance movement, smuggling clandestine messages and supplies among the local partisan groups. She was arrested, tortured, and interrogated by the Gestapo as a political prisoner and deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1943. She was recognised by Israel as Righteous Among the Nations for risking her life to save the lives of Jewish prisoners in the camps.

97. Zofia Leśniowska (1912-1943): a first lieutenant (porucznik) in the Polish Armed Forces. She was the daughter of General Władysław Sikorski. During the interwar period she was active in the Polish Red Cross and known for her passion for horse riding. After the outbreak of WW2, her father ordered her to organize a resistance movement. In 1940 she was called as an emissary to France and travelled as an underground courier, smuggling documents. She was her father’s personal secretary, coder, interpreter, and advisor. She was killed, along with her father and nine others, when their plane crashed into the sea 16 seconds after takeoff from Gibraltar Airport in July 1943.

98. Maria de Nisau (née Vetulani) (1898-1944): a Polish soldier, active in fighting for Poland’s independence. During WW2 she was a liaison soldier of the underground Home Army, where she took the pseudonym Maryna. In her apartment in Warsaw she organised a contact point and a hiding place for Jewish people. In 1944 she took part in the Warsaw Uprising. During the fighting she was wounded and treated in the hospital at Długa Street. There she was killed during a German liquidation of the Uprising hospitals.

99. Cezaria Jędrzejewiczowa (1885-1967): a scientist, art historian, and anthropologist. She was one of the pioneers of ethnology as a systematic study in Poland, and one of the first scientists to adopt empirical research in studies on folk culture. During WW2 she escaped from Poland and settled in British-held Palestine, where she co-founded the Polish Scientific Institute of Jerusalem, a sort of exile university for the soldiers of the Polish II Corps. In 1947 she moved to Great Britain, where she became one of the founding members of the Polish Scientific Society in Exile. In 1951 she became a professor of ethnography at the Polish University in Exile and soon afterwards was chosen as its rector.

100. Elżbieta Drużbacka (c.1695 or 1698/1699 – 1765): a poet of the late Baroque era in Poland, known as a ‘Slavic Sappho’ and a ‘Sarmatian Muse’. Much of her work deals with the beauty of nature – her best known work is Description of the Four Seasons (Opisanie czterech części roku). Her style was characterized as natural, simple, and pure, free of the so-called ’Macaronic language’ characteristic of her times. Most of her manuscripts, stored in the Krasińscy Library, were destroyed during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising.